Will academia buy policy-delivery fusion?

In which we learn when and why policy schools split off from schools of public administration, and ask what implications this has had for state capacity.

I’ve spent the last two days at the Center for Effective Government at the University of Chicago, where I am one of their Democracy Fellows this year. It was a fantastic experience, and one I’ll write more about later. While I was there, Emily Tavoulareas finally posted a piece she’s been mulling over for a few years, and one that I and many others of her fans have been waiting for. She finally hit publish in response to an insightful and on-target provocation by Greg Jordan-Detamore. Both question the wisdom of the division between Masters of Public Policy and Masters of Public Administration degrees, and ask how this divide both nurtures and expresses an unhelpful separation of policy and delivery in government today. So almost every moment of the last two days, I was either inside or looking at a school of public policy (my hotel room looked out right onto the roof of the beautiful Keller Center), while this debate about those very schools was taking off. Now I have the pleasure of jumping in.

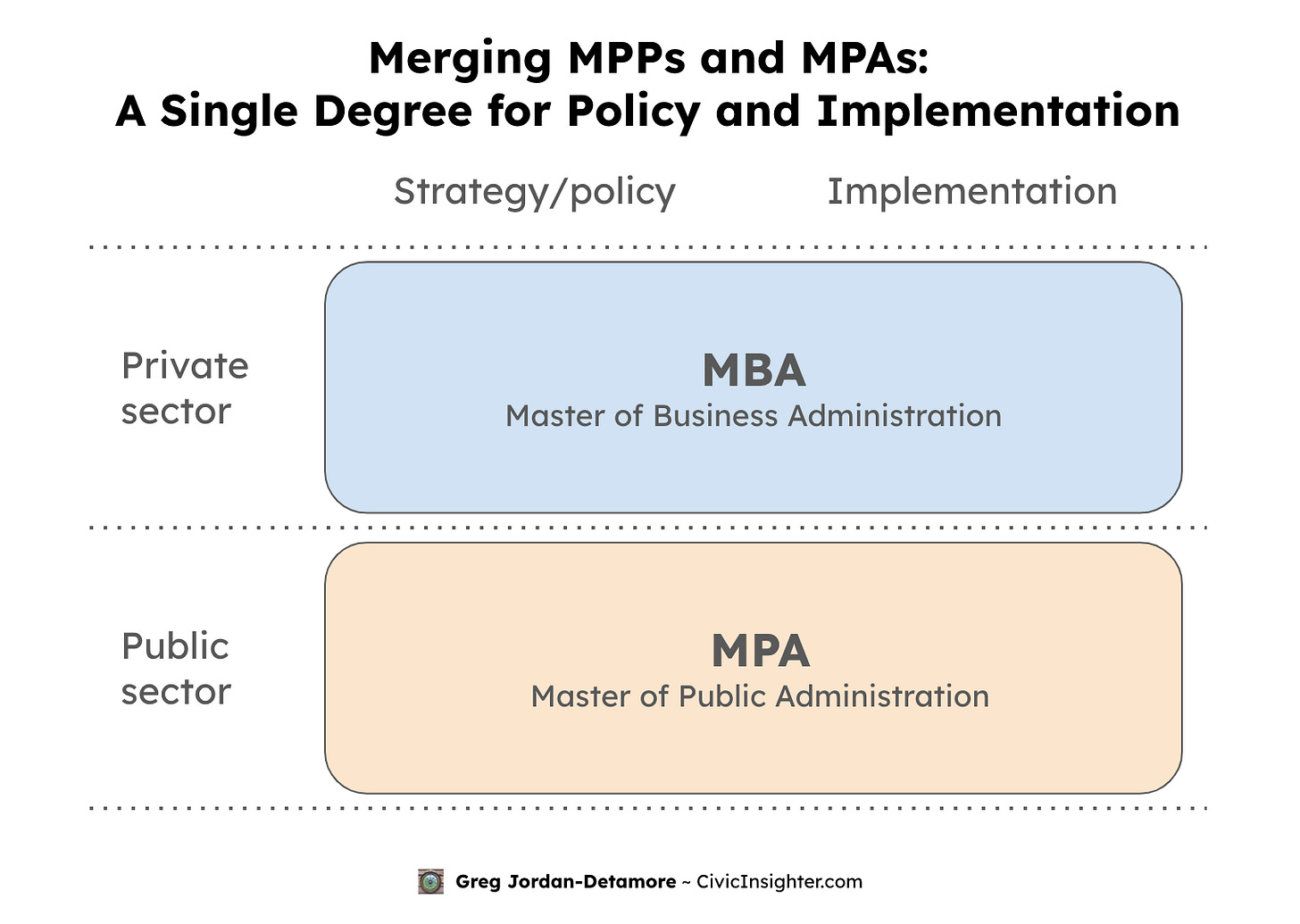

Greg starts out quoting the Network of Schools of Public Policy, Affairs, and Administration. The difference between these degrees, according to NASPPA, is that “the MPP degree focuses upon formulating and evaluating public policy while the MPA degree focuses upon the implementation of public policy.” If you know my work, you can feel me bristling. Greg and I are on the same page. “I worry,” he writes, “that the MPP vs. MPA degree split encourages a siloed mentality. There is certainly a difference between these two types of job roles, but people filling these jobs are best served with a knowledge of the fundamentals of both, especially given that many people will do both over the course of their career.”

His argument is summarized best by this graphic:

It had never occurred to me that if you’re training to work in the private sector, you’re taught strategy and implementation together, but if it’s the public sector you’re destined for, you have to choose. (I say this with the caveat that some policy schools aren’t really training the future public sector workforce – less than a quarter of grads of Harvard Kennedy School, for instance, go to work in government.) Greg notes that “Such a distinction does exist in job roles in the workplace—but the approach is that MBA programs equip their graduates with foundational knowledge and skills across the board, no matter which future path they take, as you need to see the full picture to play your part.”

But why? That’s where Emily’s observations come in. It wasn’t always this way. In the first part of the 20th century, there was only public administration, just as there is only business administration today. But after World War II, some schools of public administration became schools of public policy, and others were founded as policy schools from the beginning. Interestingly, the Ford Foundation played a part by funding this shift. (I would like to understand this better – if you have insights, please share in comments or reach out directly.) For sure, the war and the response to the Great Depression in the form of the New Deal dramatically increased the size and complexity of government, driving a need for greater specialization, but Emily teases another thought, not offered as an explanation, but a further provocation: These changes in academia began at a time when more “women and people of color were entering the workforce, often in administrative roles.” She’s not suggesting a causal link here, but it would be interesting to analyze the demographic make up of these distinct student bodies as the discipline split.

What she’s gesturing at there is the relative status of these two degrees, and of course, of the roles that people who seek these degrees end up playing in government. I’ve said the same. To quote myself in Recoding America: “At times it almost seems that status in government is dependent on how distant one can be from the implementation of policy.” I get a lot of skepticism about this point — it makes little sense in tech culture, where technical knowledge, so low down on the government ladder, reigns supreme — and I admit that as the book was going to print I worried I’d overstated it. But as soon as the book hit the shelves, people started telling me about their own experiences with this social order, and there were a lot of them. A friend who’s been a highly regarded political appointee in local and federal government for years told me the story of starting one day in a senior operations role at a federal agency and running into a former colleague in the hallways, who was delighted to see my friend and asked what his new job was. When he told him, the colleague was visibly disappointed. “Oh, is it too late to change that?” he asked.

I run the risk here of whining. The point is not that these status tiers may exacerbate inequality in the public service –- I’m not equipped to make that claim without a lot more evidence, and it’s a point I don’t intend to pursue (but would be glad for others to pick up). The point is that status drives these two fields apart and puts social, organizational, and cultural distance between groups of people who need to be working together. In very concrete terms, our institutions put both spatial and temporal distance between the two: when policy is done at a high tier of the waterfall and handed off to implementers many steps down the cascade, those teams are not only physically distant from each other but working at different times – they can’t talk to each other because they don’t even know where the other team is, and by the time the initiative in the hands of a delivery team, the policy team has already moved on to different priorities, different offices, and different roles. The point is that all of this makes for bad policy that fails to have its intended effect for the people its supposed to help. If I’m whining, it’s about that.

This burgeoning debate (and I hope it burgeons more) is intimately connected to the viability of test-and-learn approaches that show so much promise. I wrote a few weeks ago about Public Digital’s account of true policy-delivery fusion, so to speak, in implementing the UK’s Universal Credit program (sorry, programme. :)) Recall from that post that “rather than separating the policy, technology and operational delivery functions (which were even based in different parts of the country), the new team brought those disciplines together in one, co-located team.” From that foundation, and the marching orders to “deliver an intervention that means we support more people to find more work, more of the time, while protecting those who can’t work,” rather than follow the paint-by-numbers of a pre-defined policy, the team turned a few London blocks into testbeds and iterated on policy and delivery together based on how it worked for actual people in complex circumstances. If it didn’t work for one of their beta clients (my term, not theirs), they didn’t just change how they worded the question or made the font bigger on some application form, they changed the part of policy that was preventing the client from getting the needed help. The minister responsible for the service was in the room with then, reviewing the results of their real world tests, and blessing the suggested policy tweaks. This approach is the only one I know of that is suited to solve – or at least mitigate -- complex, rather than complicated problems.

I encourage to you to read more about this approach, but if I’ve gotten the gist across, my point is that you can’t do this if a separation between domains is the water you swim in, an assumption you can’t challenge because it’s taken on the character of a natural law, and if policymakers feel their status is eroded by engaging down the ladder. Recognizing that is hasn’t always been that way challenges that assumption. Ironic that it’s the Brits, whose civil service gave us the distinction between “the intellectuals” who make policy and the “mechanicals” who implement it, are the ones providing the best evidence of how garbage this distinction really is.

Emily makes another point that deeply resonates with me. We use words to mean wildly different things. Her example is the word policy, which she points out “means something entirely different in academia than it does in practice.” Coincidentally, as she was publishing her article, I was meeting with a professor of public policy to talk about the meaning of implementation. She was intrigued by my work, in part because she teaches implementation as part of the policy process, but in her lingo implementation is the part where the law or policy is passed. For her, the process ends when the President signs the paper. For me, that’s where it begins. What’s ending there, if I understand correctly, is a political process, a journey from objectively correct or at least academically blessed interventions through what various political actors will concede to, to the sometimes less-than-pretty compromise in the form of an actual bill, and ultimately an enacted law. In her story, good intentions face many perils along this journey; in mine, those perils continue, thought they are of a somewhat different nature. It was eye-opening for me to understand her definition, and I hope she felt the same about mine. I have a lot to learn, and I’m glad that as folks like Emily and Greg are raising the issue of how we train our public servants, I’m getting the opportunity to dig in on this a bit.

Both Emily and Greg’s posts do more than raise the issue; they each propose their own remedies for the problems they see, and you should read them. The committee hiring the new Dean of the Harvard Kennedy School should also read them –- in my admittedly limited experience, there’s an intriguing undercurrent of desire there to at least “surface the entanglements and dependencies,” as Emily says, between policy and implementation, and I’d love to see a new dean pull that thread with much more intention and vigor. There’s so much value in engaging in this question everywhere.

Even more food for thought: there's now a sequel to my reform proposal! Not just bringing together strategy/policy and implementation in the public sector, but bringing in the MBA too—creating one unified management degree for the public, private, and nonprofit sectors, which I call the MBPA: https://civicinsighter.com/p/meet-the-mbpa-business-public-administration

I'd be curious: Have you had conversations with faculty or students at business schools re: state capcity, Recoding America, etc.?