Channel your inner Marie Kondo

The life-changing art of identifying and eliminating policy clutter

I originally wrote this for The States Forum in June but am reposting it here ICYMI. The intended audience is state legislators.

As the pandemic put millions of people out of work, states developed a backlog of unemployment insurance claims. Many governors blamed COBOL, a programming language developed in 1959 and still in widespread use. But COBOL was not the real culprit. In California, where I chaired a task force to clear the state’s backlog, parts of the system using COBOL chugged along with remarkable resilience. And although about half of the states had modernized their mainframes prior to the pandemic, those states fared no better on average. If retiring legacy code doesn’t fix the problem, something else is holding our systems back from resilience and scalability.

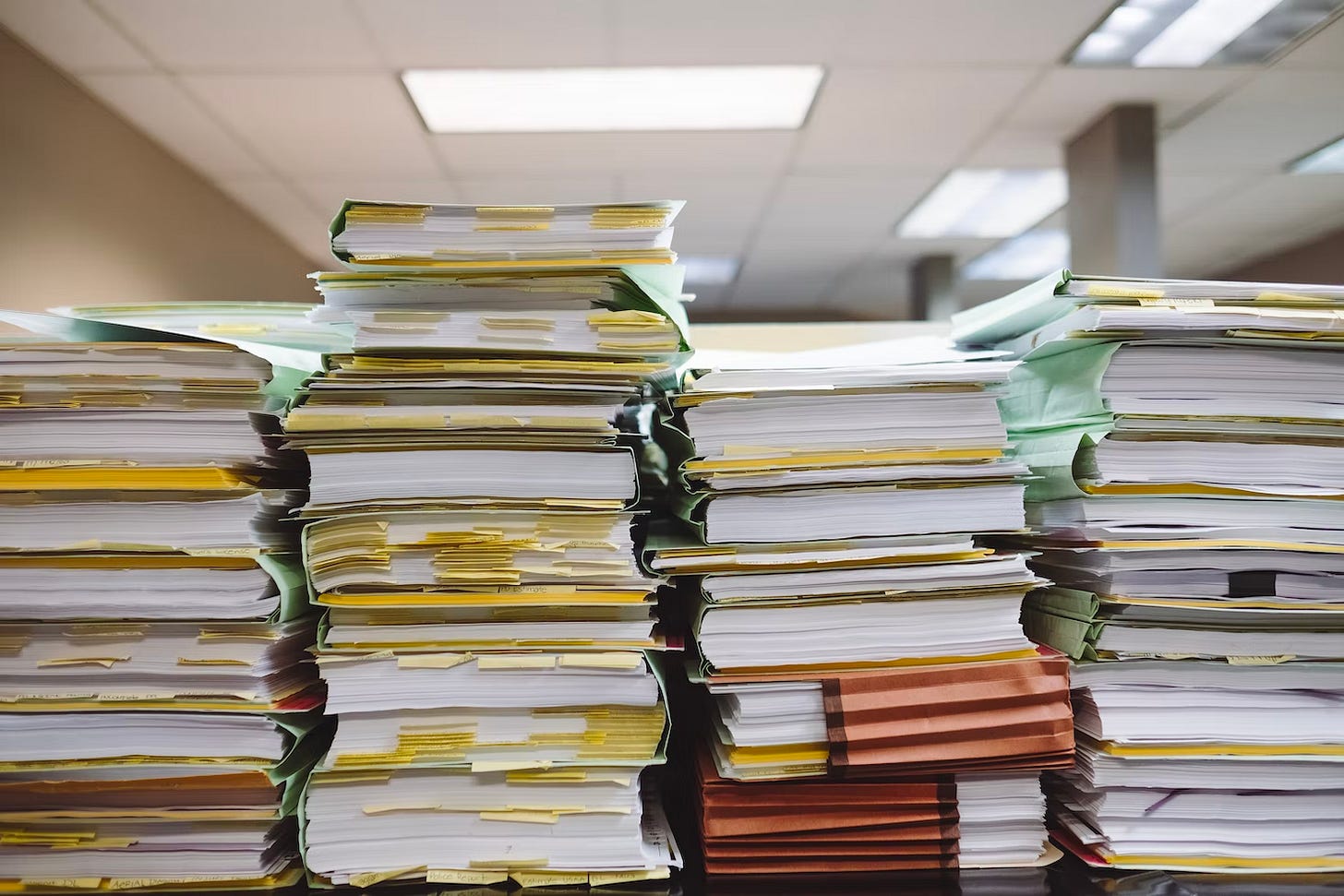

New Jersey’s Labor Commissioner Robert Asaro-Angelo put the blame where it belongs. Called to testify to the legislature about the backlog, he brought along several boxes labeled “7,119 pages of active UI regulations” and placed them prominently in view of the members. “We are putting duct tape and Band-Aids on outdated policy,” he told the legislators. The technological issues his agency was grappling with were just a symptom. The underlying cause was the complexity and sheer volume of rules and regulations computer systems were supposed to operationalize.

Asaro-Angelo’s team ultimately worked through the backlog, and analysts later called their response among the best in the nation. But the problems that make state systems fragile and inadequate in times of steep unemployment have not been solved. Until state legislators (and the U.S. Department of Labor) recognize their role in that dysfunction and start to address the statutory and regulatory complexity, they won’t be.

Regulatory cruft is not unique to unemployment insurance. In many domains, new rules are layered upon old ones; seldom is there a corresponding effort to reconcile or eliminate outdated, redundant, or conflicting provisions. This “policy clutter” creates a dense and often contradictory web that makes effective implementation difficult. With the right competencies, the executive branch can shield the public from some of that complexity, but without effective partners in the legislature, it can accomplish only so much. We need lawmakers eager to channel their inner Marie Kondo to do the life-changing work of tidying up.

Making matters worse, a different kind of policy clutter hampers the competencies and capacities agencies need to address the problem. Civil-service rules in many states constrain and prolong the hiring process, effectively turning away the necessary workforce. Procurement is no better. When our task force started work in July 2020, the California Employment Development Department (EDD) was about to request proposals for a “business system modernization,” a project the department had already been working on for 11 years. To clarify, 11 years was not how long it took for a vendor to develop the new system; it took 11 years for the state to be ready to solicit bids. It would take a few more to collect and review those bids before awarding a contract. Only then would the work start, at which point the requirements collected over a decade earlier were sorely out of date. The glacial pace is due to an inscrutable web of procurement and contracting rules. Agencies subject to such regulations are largely powerless to change them on their own.

Such rules almost always start with good intentions. But their impact is often at odds with those values. In 2017, for instance, San Francisco imposed a ban on doing business with states that failed to support LGBTQ and abortion rights. The city even prohibited certain of its employees from traveling to those states on city business, even to woo companies to relocate to San Francisco.

The policy became a burden, partly because adherence was so impractical, with staff repeatedly applying for waivers to circumvent it, and partly because every acquisition, from computers to toilet paper, required paperwork proving compliance with the ban. In one case, an LGBTQ-owned venture that had been doing business with the city for years was cut from its supplier rolls when it was bought by a company in one of the 30 banned states. Prices went up, as suppliers who still qualified realized how much less competition they faced. The law was cited as one of the reasons a public toilet came with a $1.7 million price tag. When it was repealed seven years later, not only had the ban failed to move social policy in any of the banned states, its effect on city finances was disastrous and it harmed some of the very stakeholders it was meant to help. Policies like this also hurt the reputation of blue-state governance.

Conventional wisdom says the job of a legislator is to legislate. Most of the laws created for executive-branch agencies are either mandates or constraints (something they must do or can no longer do). But agencies are now drowning in these rules. As one leader put it, “It’s like I’m supposed to run a marathon, but I have to ask ‘Mother, may I?’ every step of the way.”

The best state lawmakers recognize that adding mandates and constraints is just one tool at their disposal. Because legislation doesn’t need to add to the clutter; in fact, it can be written to clean up the mess. “Clear the clutter” might not sound like a winning agenda with your constituents, but they’ll feel the effects every time they do business with the state.

As recognition of policy clutter has grown, so have the tools used to address it. Even a large and expert legislative staff can fail to grasp the intricate web of laws, policies, and regulations governing a single issue when it spans dozens or hundreds of documents and thousands of pages. But large language models (LLMs) perform impressively at these tasks.

One such model is the Statutory Research Assistant (STARA), developed by the Stanford RegLab. STARA is an automated system capable of performing accurate “statutory surveys”—compilations of all legal provisions relevant to a particular issue—along with detailed annotations and reasoning. A recent research paper by Daniel Ho and others details some of the ways his team, in collaboration with public sector leaders, have used the tool.

One example examined the federal criminal code. As Ho and his co-authors write: “Title 18 of the U.S. Code is notoriously dense and complex, consisting of 1,510 sections that span tens of thousands of pages of text. While Title 18 is the main federal criminal code, there are federal offenses that are not included in Title 18.” Justice Department officials have been trying to get Congress to recognize the negative consequences of this complexity since 1982, when they first tried to count the number of federal crimes. After two years of combing through statutes, they could arrive only at an educated guess (3,000 crimes). In 1998, the American Bar Association tried its hand, concluding that the number was likely higher than what Justice had estimated but failing to return an authoritative figure. In 2019, researchers at the Heritage Foundation tried again, under the banner of “Count the Code,” by searching for phrases—“punished by a fine” or “shall be fined or imprisoned”—commonly associated with criminal offenses. This time, they confidently put forward a number: 1,510. But STARA, leveraging more sophisticated technology, recently identified 2,305 criminal provisions (53% more) with 98% precision (yes, they checked)—nearly 800 more than previously documented.

Although a necessary first step, gaining an accurate picture of the problem does nothing to reduce the complexity of the criminal code. Congress still needs to act, and there are very good reasons it should do so. When prosecutors cannot easily identify all the relevant criminal statutes, it’s difficult to ensure consistent and fair application of the law across different cases and jurisdictions. Without knowing the full scope of criminal provisions, the Justice Department may struggle to prioritize enforcement areas or to allocate resources effectively. It’s nearly impossible to train prosecutors and investigators in laws they cannot systematically identify or access. And complexity is expensive. The system would be more effective and more equitable and cost less if our elected leaders could produce a moderately simpler set of rules, one that rationalizes choices made over time into something more straightforward.

Congress may not be ready to act, but states are in a position to tackle their own criminal codes—and could start by coming up with a credible count, as the Department of Justice did. Representative Marie Gluesenkamp Perez from Washington’s 3rd district caused a stir when she highlighted how confusing and restrictive licensing regulations resulted in childcare facilities being told they couldn’t serve fresh fruit to the kids in their care. Policy clutter has become a burden across so much of modern life; here are a few areas to consider.

Housing: Developers often face overlapping or conflicting requirements, from state-level zoning statutes to related environmental regulations. These can delay projects and drive up costs. The political pressure to act on these conditions is mounting as the conversation around abundance enters the mainstream, but action requires actually understanding this tangle of rules. Mapping state-level zoning statutes and related environmental regulations could highlight redundant or overly restrictive provisions that could be simplified or removed to accelerate housing development.

Education: State education codes are notoriously detailed and expansive, encompassing curriculum requirements, teacher certifications, standardized-testing rules, and funding formulas. Over time, these layers of policy create confusion and administrative inefficiency, and restrict innovation in education. Identifying outdated mandates, conflicting curriculum standards, and unnecessary administrative obligations could simplify educators’ and administrators’ workloads.

Healthcare: Hospitals, clinics, nursing homes, and assisted-living facilities must adhere to an intricate web of state health codes, safety regulations, staffing requirements, and licensing standards, which often overlap with federal rules. The complexity can result in inconsistent enforcement and high compliance costs. Removing conflicting or duplicative regulations, including harmonizing reporting requirements across levels of government, could lower healthcare costs and improve service-delivery efficiency.

Professional and occupational licensing: In occupations ranging from cosmetology and interior design to nursing and teaching, the licensing process is typically regulated at the state level and often entails outdated or conflicting criteria. A statutory review could reveal outdated or conflicting licensure criteria, providing legislators opportunities for streamlining and consolidation.

Insurance and financial regulation: Some states have notoriously dense insurance codes, creating a convoluted compliance landscape for companies and confusion among consumers. Removing unnecessary complexity or conflicts could improve competition and better protect consumers.

This list of policy-clutter opportunities admittedly glosses over the reality of politics and change. A certain amount of cleanup will be relatively uncontroversial, slowed only by a natural human tendency to prefer the comfort of the status quo. Other proposed changes will face self-interested opposition and will require courage, and often compromise. Navigating those trade-offs requires leadership. Here are a few tips to keep in mind.

Explore the landscape of opportunity. As these tools mature, statutory surveys will be increasingly easy and accessible. Try running these models in a number of areas before deciding where to dive in.

Start with test cases. As you identify policies that may benefit from simplification, start with something less publicly visible, so that you can learn outside of the spotlight. Many hot-topic areas (such as permitting) are ripe for simplification; getting some trial-and-error practice under your belt first will help you get these high-stakes cases right.

Model comfort with LLMs. STARA isn’t yet available on the web, but teams like the RegLab are actively engaging partners and models like ChatGPT’s Deep Research are commercially available and well worth the cost. Encourage your staff to become familiar with their capabilities and try them out for yourself. Upload sections of the federal or state code; tell the model what you’re trying to achieve; ask for recommendations for statutory and regulatory change. Support pilot programs within legislative research departments that explore potential AI applications.

Engage agencies. Encourage state agencies to recommend areas where streamlining regulations could make systems more robust and scalable. Encourage them to use LLMs toward this effort, but don’t require it. Use their suggestions as a jumping-off point for further LLM-powered inquiry to understand the full scope of regulations impacting their work, and keep lines of communication open. Support initiatives to train public servants in these skills and to bring in individuals with the needed expertise.

Let LLMs help you think before you legislate. It’s often easier and more appealing to craft a new bill than to troubleshoot or downsize existing statutes, but the latter can be far more effective. When proposing new policies, actively consider their potential impact on existing regulations and the capacity of state agencies to implement them effectively. Ask models: How will this interact with the current layers of policy? What can be achieved through regulatory and/or practice change, without a new bill?

Leverage user research. If your state has a digital services team, they likely conduct unstructured, observational research that can complement the insights of LLM analysis by revealing how the rules play out in real-world situations. Ask them for help with methods of understanding the real-world impact of policies and identify pain points in service delivery.

If you want to become a leader in applying Marie Kondo decluttering to your state, the first principle is to not add to the problem. I’ve lost count of how many times legislators have admitted to me their regret over introducing a bill that sounded good at the time, but only added more complexity to an already mind-bogglingly complex system, with unwelcome consequences. Legislators need to undo these mistakes, and those of their predecessors, using powerful new tools like STARA to analyze opportunities for rationalization and simplification—and, ultimately, repeal unhelpful laws and regulations.

Rationalizing existing policies can move legislatures beyond merely reacting to crises, and toward building a more responsive, effective, and ultimately more trustworthy government for the people they serve. The thousands of pages of regulations Commissioner Asaro-Angelo made visible at his hearing are mostly invisible to the rest of us. But the clutter they represent is real, and a drag on your state. Let that image serve as a constant reminder that, for a legislator in a country about to turn 250 years old, right now, less is more.

Great post! One little clarification: zoning is generally in the purview of local governments, not states (which makes it worse - capacity is a *huge* issue at the local level). There’s a great project underway to digitize these regulations: https://www.zoningatlas.org/. Hopefully the first step in the sort of process you describe here.

Policy clutter is the hidden nightmare of policy implementation. Sometimes clutter is caused with the best of intentions. A small change is made because of regulatory and political constraints make comprehensive changes impossible. These small changes are then never pruned for utility and not considered in context of how multiple small changes affect the entire system.

This is compounded by fear of change. The idea that if we make a change, are we making a mistake or I fought hard for that, I don't want to give it up? They forget that the status quo is working poorly, and is a mistake itself.

Then there are people that benefit from complexity. They have the ability to navigate the system better than anyone else because they understand it.

Finally, legislators don't have press conferences for legislation that simplifies a program. Simplification isn't something easily quantified or understood, and it is a lot of hard work. Using STARA to inventory elements of a vast regulatory network could be very beneficial.

I experienced all of these problems (except for the last one) in a non-regulatory effort when I oversaw a project to redesign and simplify the SNAP (Food Stamps) eligibility documents in California. I'm sure that if this were a regulatory effort, the stakes would be much higher and the intransigence would be even worse.

Of course this type of work shouldn't be confused with the DOGE/Trump effort to reduce regulations. They really just want to eliminate programs they don't like.